Just reading Shaun Richard's excellent blog on this. Barlays is being forced to get up to a 3% capitalisation level. This means that it currently has loaned out £427 billion too much in loans.

That 0.6% growth we experienced in Q1 2013 took GDP up to £365 billion. Gives you an idea of the scale of the UK's private debt problem when a single major bank has loaned out more than a good quarter of growth and only holds 2% of that in deposits. This is an important insight into how banking really works, and why even this supposed drastic action by the Bank of England is a drop in the bucket.

The under-regulated banking sector is at the heart of the global economic crisis because it is their that the mad policies of free-marketeers are most perfectly implemented - and to be clear Labour have been as complicit in this as the Tories.

Even under the new levels set by the BoE Barclays only requires 3% capitalisation.

Deregulation, debt, corruption, recession, and the Second Great Depression. Something must be done!

30 Jul 2013

What is an economic recovery?

Some definitions of "Economic Recovery"

So let's take a brief look at some of the relevant quantities: GDP, unemployment and inflation.

We already know that GDP is rising very slowly, and that many commentators are saying the the 0.6% growth of Q1 2013 is unsustainable. If anything the fall in real wages is likely to contribute to reduced demand for basics. I've dealt with recent GDP trends recently. And with changes in the way GDP is adjusted for inflation which have resulted in higher GDP estimates since 2011.

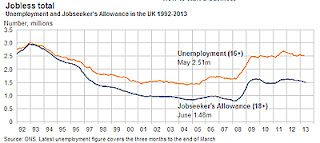

Unemployment is still or around the levels that resulted directly from the 2008 crisis. There was a spike in 2011 that subsided, leaving us at the levels of mid 2009. The trend seems to be flat at present. These figures do not encompass the under-employed either. This is a growing problem pointed to by some pundits. With the workforce being pushed into zero hour contracts and so on we're seeing the workforce unable to make enough money to make ends meet - they want to work more but can't. And many of these people have to avail themselves of the Landlord Subsidy (aka Housing Benefit) in order to keep a roof over their heads.

Inflation has jumped about quite a bit over the last few years - especially the RPI which includes housing costs. But generally speaking it has been higher than government targets and higher than wage rises. Indeed wage rises have been below inflation for a long time now. The ONS is reported as saying the current wage levels are about the same as in 2003. The recent Bank of England inflation report said that inflation was likely to remain above its target of 2% until 2016, suggesting that real wages will continue to fall.

On the bright side, and I'm sure the government see this as a positive, driving wages down ought to help with the unemployment figures in theory. Lower wages means that firms are more likely to take on new staff. Unfortunately with demand stagnant there is no real potential for expansion in the economy as a whole.

These are broad brush-stroke figures. Not the kind of detailed info that professional economic pundits use. That said I do not see a recovery here. I see stagnation. It might be argued that I expect to see stagnation because of the economists who influence my thinking. But if someone else can see a recovery in these figures then I'd be interested to know how.

An economic recovery is the phase of the business cycle following a recession, during which an economy regains and exceeds peak employment and output levels achieved prior to downturn. A recovery period is typically characterized by abnormally high levels of growth in real gross domestic product, employment, corporate profits, and other indicators. - Wikipedia.

A early expansionary phase of the business cycle shortly after a contraction has ended, but before a full-blown expansion begins. During a recovery, the unemployment rate remains relatively high, but it is beginning to fall. Real gross domestic product has begun to increase, usually rapidly. However, because the contraction remains fresh in the minds of many, it may not be immediately clear that the trough of the contraction has been reached. - Economic Glossary.

Phase in an economic cycle where employment and output begin to rise to their normal levels after a recession or slump. - Business Dictionary.

A period of increasing business activity signaling the end of a recession. Much like a recession, an economic recovery is not always easy to recognize until at least several months after it has begun. Economists use a variety of indicators, including GDP, inflation, financial markets and unemployment to analyze the state of the economy and determine whether a recovery is in progress. - Investopedia.

So let's take a brief look at some of the relevant quantities: GDP, unemployment and inflation.

| source: UK Public Spending |

|

| Source: BBC |

|

| Source: BBC |

On the bright side, and I'm sure the government see this as a positive, driving wages down ought to help with the unemployment figures in theory. Lower wages means that firms are more likely to take on new staff. Unfortunately with demand stagnant there is no real potential for expansion in the economy as a whole.

These are broad brush-stroke figures. Not the kind of detailed info that professional economic pundits use. That said I do not see a recovery here. I see stagnation. It might be argued that I expect to see stagnation because of the economists who influence my thinking. But if someone else can see a recovery in these figures then I'd be interested to know how.

29 Jul 2013

Did We really Avoid Double Dip Recession?

In her article The ‘secret deflator’ used to fiddle the GDP figures, Merryn Somerset Webb of Money Week, points out an oddity in the way the ONS calculates inflation for adjusting GDP changes. In this graph the GDP adjusted by the Retail Price Index (RPI one of the main measures of inflation, in blue) is compared to GDP adjusted by the ONS figures (grey).

Note that since 2011 the figure used for inflation has been very much lower than the RPI. So at present the ONS figures on GDP are much higher than they would be if they used the RPI figure for inflation.

In a comment on the blog by Shaun Richards points to another blog, Why was the calculation of UK GDP changed? Lower recorded inflation so higher growth?, where he explains the difference. It is because in 2011 the ONS made the decision to switch from using a figure based on the RPI to a figure based on the Consumer Prices Index (CPI). He cites the ONS:

However, CPI has a number of advantages over the RPI for this purpose, as discussed below, and the international guidance is clear that the CPI should be using [sic] in preference.

And he comments:

"Missing in the list of advantages is that fact that the CPI tends to give a lower number for inflation than the RPI sometimes substantially lower!"

One of the main reasons for the CPI giving lower figures is that RPI includes housing costs. And housing costs have been steadily rising for years now due to the chronic shortage of housing in the UK. The logic of excluding the cost of housing escapes me.

Had we continued to use the same measure of inflation to adjust the figures throughout, then GDP growth would still be negative. Not on did we not avoid a double dip recession, but we are still in that recession! Ah the joy of statistics.

Had we continued to use the same measure of inflation to adjust the figures throughout, then GDP growth would still be negative. Not on did we not avoid a double dip recession, but we are still in that recession! Ah the joy of statistics.

All credit to the two authors whose work I am citing here. Please read the original stories. It is worth reading the comments on both blogs for further informed comment on this issue.

27 Jul 2013

Government Expenditure and the Long recession

This is a very interesting chart from the IMF's World Economic Output Report (April 2013).

What is shows is that in most cases, and certainly in the UK, government expenditure was only slightly above average leading up to the recession (USA being the exception and they were fighting two major overseas wars). Government expenditure seems not to be tightly correlated with the recession. Which is not what we'd expect if the government's rhetoric were true. Instead the figures contradict all the rhetoric about profligacy in the previous government - and yet the opposition seem unable to capitalise on this, but that's another story. These figures are what we'd expect if private debt were the driver of the recession, and in the years leading up to the recession various governments had begun to believe that their economies were now literally exempt from boom and bust (what we might call the Greenspan fallacy).

The thing to note however is that this recession is lasting a long time. And correlated with this is post-recession expenditure well below averages. That is to say that cuts in government spending are correlated with an extended recession. Of course correlation is not causation, but it would be very interesting to look more closely at this.

In the past governments generally continued to steadily increase their spending post-recession. In the world's advanced economies government spending is considerably below the average at present. In emerging market economies (the economies that are still growing at an appreciable rate) government expenditure is presently above average.

One of the factors is that government revenues have collapsed in this recession in a way that is almost unprecedented. With the debt fuelled economic bubble, government tax takes were high for a lengthy period and governments, especially the UK government, became complaisant about spending at boom levels. When the banks collapsed it was necessary to borrow a lot of money to prop them up, raising interest costs and decreasing the amount available to spend.

What is shows is that in most cases, and certainly in the UK, government expenditure was only slightly above average leading up to the recession (USA being the exception and they were fighting two major overseas wars). Government expenditure seems not to be tightly correlated with the recession. Which is not what we'd expect if the government's rhetoric were true. Instead the figures contradict all the rhetoric about profligacy in the previous government - and yet the opposition seem unable to capitalise on this, but that's another story. These figures are what we'd expect if private debt were the driver of the recession, and in the years leading up to the recession various governments had begun to believe that their economies were now literally exempt from boom and bust (what we might call the Greenspan fallacy).

The thing to note however is that this recession is lasting a long time. And correlated with this is post-recession expenditure well below averages. That is to say that cuts in government spending are correlated with an extended recession. Of course correlation is not causation, but it would be very interesting to look more closely at this.

In the past governments generally continued to steadily increase their spending post-recession. In the world's advanced economies government spending is considerably below the average at present. In emerging market economies (the economies that are still growing at an appreciable rate) government expenditure is presently above average.

One of the factors is that government revenues have collapsed in this recession in a way that is almost unprecedented. With the debt fuelled economic bubble, government tax takes were high for a lengthy period and governments, especially the UK government, became complaisant about spending at boom levels. When the banks collapsed it was necessary to borrow a lot of money to prop them up, raising interest costs and decreasing the amount available to spend.

25 Jul 2013

0.6% GDP Growth in Context

The Q1 2013 GDP figures are out. 0.6% growth would probably have been seen quite favourably in the pre-2008 world.

Had growth continued on the trend of those 52 years then we'd expect GDP in this quarter to be ca. £415 billion. What we have is GDP of ca. £365 billion. A shortfall of £50 billion this quarter. This means we're about 12% below the GDP we'd expect given the 50 year trend. And note that the dotted red and solid blue lines are still diverging which means that we are still drifting away from the long term trend of GDP growth.

We are not making up the shortfall and the shortfall is increasing. Until we turn this around and start to move back towards the trend we have two options:

But it doesn't make up any lost ground. It's about average and doesn't therefore constitute a recovery. The red line shows quarterly GDP seasonally adjusted from 1955-2007. The dotted red trend line is a shallow exponential curve with an R2 of 0.9927 (and extended out 20 quarters from the end of 2007).

|

| Click image to embiggen |

Had growth continued on the trend of those 52 years then we'd expect GDP in this quarter to be ca. £415 billion. What we have is GDP of ca. £365 billion. A shortfall of £50 billion this quarter. This means we're about 12% below the GDP we'd expect given the 50 year trend. And note that the dotted red and solid blue lines are still diverging which means that we are still drifting away from the long term trend of GDP growth.

We are not making up the shortfall and the shortfall is increasing. Until we turn this around and start to move back towards the trend we have two options:

- Shut up about 'recovery'.

- Redefine the long term trend to be roughly zero growth.

Since the government are crowing about 0.6% growth we can probably assume that they have abandoned the idea of recouping our losses, and have accepted that the lost income of the last 5 years is not recoverable. The UK economy has simply lost 12% of it's value (so far) and is continuing on a new trend of flat growth.

The dotted blue line is a linear regression of the figures from 2010-2013 - since the recession officially ended.

Interesting if you draw a straight line through 2010-2013 the line does indeed slope up and gets to the same level as Q1 2008 (£375 bn) in about 2018. So the people who were predicting 10 years of depression 2 or 3 years ago seem to be about tight. At that point the long term trend line predicts GDP of £475 bn. So we will be 21% below trend and counting.

GDP growth was 0.6% in Q1 2013. But from 2011 to 2013 it was only 0.06%.

The dotted blue line is a linear regression of the figures from 2010-2013 - since the recession officially ended.

|

| Click image to embiggen |

Interesting if you draw a straight line through 2010-2013 the line does indeed slope up and gets to the same level as Q1 2008 (£375 bn) in about 2018. So the people who were predicting 10 years of depression 2 or 3 years ago seem to be about tight. At that point the long term trend line predicts GDP of £475 bn. So we will be 21% below trend and counting.

GDP growth was 0.6% in Q1 2013. But from 2011 to 2013 it was only 0.06%.

23 Jul 2013

Everyone Pays Taxes and Everyone Benefits from Welfare.

In the UK it's easy to end up feeling guilty about living on social welfare. Most people don't choose that life but have it thrust on them and do what they can to get out of it. But the media seem to join with politicians in wanting us to believe that only income earners pay tax or that income tax is the only tax. It is not. Income tax is only about 25% of the government's income.

Everyone in the UK pays VAT. This is a 20% surcharge on goods and services. Food is excluded, but most other things you buy include tax. of the so-called indirect taxes, VAT alone accounts for about 17% of government revenue. Other taxes such as alcohol duty affect nearly everyone in the UK. So even if you pay no income tax because you have no income, you still pay taxes. So this mantra 'my taxes are paying your wages' is inaccurate. Everyone pays tax.

What's more the benefit system represents a subsidy on many sectors. For example, despite the economic crisis and falling house prices, rental accommodation has steadily increased in cost. Housing Benefit is paid to many people who work as well as those with no regular income. This is a government subsidy of some £17 billion per year to the housing sector. And the scale of it helps to keep rental costs high.

The alternative to subsidised housing in the short-term, however, would not be lower rental costs. No, it would be mass homelessness, because demand so outstrips supply that even without subsidies the demand would be more than could be supplied.

The housing shortage has been left to the market to fix, but the market has a vested interest in not fixing the problems, in keeping supply restricted so as to keep rents high and rising. Especially when other forms of investment are struggling during the Long Recession. Some estimates suggest the UK needs 2 million more houses as of now. Immigration keeps the population growing, despite the baby boomer bulge now squeezing out of the top of the population pyramid.

At present it seems that the UK government are content to allow this situation to continue on the landlord side, probably because so many of the government are themselves landlords. But they are undermining it from the tenant side and so homeless and poverty are about to start rising.

Since people who accept social welfare payments tend to spend all of it, the government also subsidises supermarkets and pubs and all sorts of other businesses. About £167 billion per year is spent by the DWP and most of that finds it's way back into circulation in supermarkets, shops and pubs - and a percentage makes its way back to the government as tax, but most of it is either spent again (hence the infamous multiplier effect) or saved. Just imagine what would happen if this subsidy was suddenly withdrawn. On top of homelessness and all the other problems of poverty, many of the struggling businesses would go bankrupt. More especially in the present since so many companies are teetering on the edge of solvency anyway, or are zombie companies, technically insolvent but allowed by banks to continue trading because banks, themselves close to insolvent, can't afford to lose the revenue stream.

I've often wondered why we call social welfare payments "benefits" in the UK. After all it seems strange to think in terms of the benefits of losing your job or becoming too ill to work. Social welfare is more of a consolation for misfortune. But society as a whole does benefit from supporting those people who cannot work. The benefit is for society as a whole, not one particular individual - hence in most places it is called social welfare. Keeping those who lose jobs or become ill in the loop of society makes the transition back into work smoother. It keeps people from becoming homeless for example, or from completely dropping out of society.

Far from being a burden on society, welfare is a massive subsidy that is helping to keep the nation afloat in a crisis. It's the remains of a from of economic thinking that is not based in the fantasy of the market will solve all our problems. Social welfare is still predicated on the idea that the market will not provide fairness and as such is one of the few remaining counter-weights to the fantasies of NeoLiberalism. It also provides a cohesive factor when centripetal economic forces are sending many people to the margins of the economy and beyond.

But make no mistake. The social welfare system is under attack by NeoLiberals aided and abetted by mainstream media who are largely uncritical of the NeoLiberal agenda. The real benefits of social welfare are systematically hidden and mirages of disadvantage are being created. The mythical "tax-payer" is told they are missing out when someone else gets welfare. The working person who has seen 40 consecutive months of contracting wages only knows that their money doesn't go as far as it used to. It's all too easily for them to buy into blaming the social welfare system, because the government are spinning it with everything they've got. Working people are squeezed because of government policies which are designed to maximise the wealth of the wealthy at any cost, but the government is seeking to deflect responsibility away from themselves. And such governments traditionally blame the poor for being poor. Being rich is a measure of moral goodness in their worldview, and being poor is laziness at best. There is not enough critique of these kinds of assumptions, no substantive opposition from the left, and precious little public discourse which does not come from spin doctors.

This same attitude means that political parties are unwilling to consider alternatives to the status quo of NeoLiberal values and NeoClassical economics. And not just the traditionally right-wing parties, but the left as well. The possibility that instead of using QE to directly subsidise banks with no great effect on the economy, that we might use it to stimulate the economy by giving money to individuals, especially poor individuals is not even considered. Not even by the left. Sadly I no longer see any possibility of the Modern Debt Jubilee taking place. Or anything like it. Combating government propaganda, combined with the propaganda of big business, is not yet effective - despite the state of the UK economy there is no sign of anyone offering a credible alternative.

Everyone in the UK pays VAT. This is a 20% surcharge on goods and services. Food is excluded, but most other things you buy include tax. of the so-called indirect taxes, VAT alone accounts for about 17% of government revenue. Other taxes such as alcohol duty affect nearly everyone in the UK. So even if you pay no income tax because you have no income, you still pay taxes. So this mantra 'my taxes are paying your wages' is inaccurate. Everyone pays tax.

Housing Benefit is a government subsidy of some

£17 billion per year to the housing sector.

What's more the benefit system represents a subsidy on many sectors. For example, despite the economic crisis and falling house prices, rental accommodation has steadily increased in cost. Housing Benefit is paid to many people who work as well as those with no regular income. This is a government subsidy of some £17 billion per year to the housing sector. And the scale of it helps to keep rental costs high.

The alternative to subsidised housing in the short-term, however, would not be lower rental costs. No, it would be mass homelessness, because demand so outstrips supply that even without subsidies the demand would be more than could be supplied.

The housing shortage has been left to the market to fix, but the market has a vested interest in not fixing the problems, in keeping supply restricted so as to keep rents high and rising. Especially when other forms of investment are struggling during the Long Recession. Some estimates suggest the UK needs 2 million more houses as of now. Immigration keeps the population growing, despite the baby boomer bulge now squeezing out of the top of the population pyramid.

At present it seems that the UK government are content to allow this situation to continue on the landlord side, probably because so many of the government are themselves landlords. But they are undermining it from the tenant side and so homeless and poverty are about to start rising.

Since people who accept social welfare payments tend to spend all of it, the government also subsidises supermarkets and pubs and all sorts of other businesses. About £167 billion per year is spent by the DWP and most of that finds it's way back into circulation in supermarkets, shops and pubs - and a percentage makes its way back to the government as tax, but most of it is either spent again (hence the infamous multiplier effect) or saved. Just imagine what would happen if this subsidy was suddenly withdrawn. On top of homelessness and all the other problems of poverty, many of the struggling businesses would go bankrupt. More especially in the present since so many companies are teetering on the edge of solvency anyway, or are zombie companies, technically insolvent but allowed by banks to continue trading because banks, themselves close to insolvent, can't afford to lose the revenue stream.

Those receiving welfare payments could think of themselves as low-paid civil servants distributing government subsidies to local businesses.

I've often wondered why we call social welfare payments "benefits" in the UK. After all it seems strange to think in terms of the benefits of losing your job or becoming too ill to work. Social welfare is more of a consolation for misfortune. But society as a whole does benefit from supporting those people who cannot work. The benefit is for society as a whole, not one particular individual - hence in most places it is called social welfare. Keeping those who lose jobs or become ill in the loop of society makes the transition back into work smoother. It keeps people from becoming homeless for example, or from completely dropping out of society.

Far from being a burden on society, welfare is a massive subsidy that is helping to keep the nation afloat in a crisis. It's the remains of a from of economic thinking that is not based in the fantasy of the market will solve all our problems. Social welfare is still predicated on the idea that the market will not provide fairness and as such is one of the few remaining counter-weights to the fantasies of NeoLiberalism. It also provides a cohesive factor when centripetal economic forces are sending many people to the margins of the economy and beyond.

But make no mistake. The social welfare system is under attack by NeoLiberals aided and abetted by mainstream media who are largely uncritical of the NeoLiberal agenda. The real benefits of social welfare are systematically hidden and mirages of disadvantage are being created. The mythical "tax-payer" is told they are missing out when someone else gets welfare. The working person who has seen 40 consecutive months of contracting wages only knows that their money doesn't go as far as it used to. It's all too easily for them to buy into blaming the social welfare system, because the government are spinning it with everything they've got. Working people are squeezed because of government policies which are designed to maximise the wealth of the wealthy at any cost, but the government is seeking to deflect responsibility away from themselves. And such governments traditionally blame the poor for being poor. Being rich is a measure of moral goodness in their worldview, and being poor is laziness at best. There is not enough critique of these kinds of assumptions, no substantive opposition from the left, and precious little public discourse which does not come from spin doctors.

This same attitude means that political parties are unwilling to consider alternatives to the status quo of NeoLiberal values and NeoClassical economics. And not just the traditionally right-wing parties, but the left as well. The possibility that instead of using QE to directly subsidise banks with no great effect on the economy, that we might use it to stimulate the economy by giving money to individuals, especially poor individuals is not even considered. Not even by the left. Sadly I no longer see any possibility of the Modern Debt Jubilee taking place. Or anything like it. Combating government propaganda, combined with the propaganda of big business, is not yet effective - despite the state of the UK economy there is no sign of anyone offering a credible alternative.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)